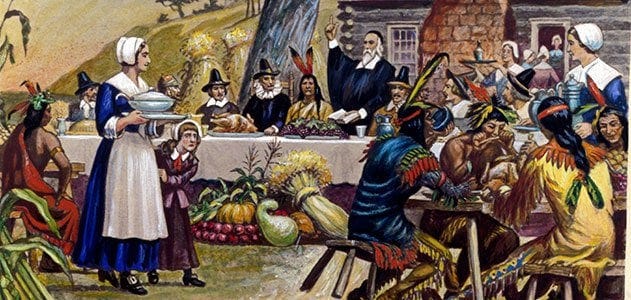

Thursday marks the American Thanksgiving, a tradition older than me, which makes it pretty old. While Southerners may lay claim to Jamestown holding the first thanksgiving, the American tradition began when the 53 survivors of the Mayflower journey to the New World invited 90 Wampanoag Indians over for a celebration as the settlers thanked the Lord for their first harvest. It was three days of peace, love and harmony.

Now for a disclosure. My ancestors include Francis Eaton, who signed the Mayflower Compact. That’s according to my big sister who has never once in my 69 years lied to me. I look up to her from afar.

The Pilgrims stole no one’s land and had no slaves. That’s according to their critics.

Native Voices reported, “AD 1620: English Pilgrims settle on Wampanoag land.

“Pilgrims settle at what is now known as Plymouth, Massachusetts, on Cape Cod near the abandoned village of Pahtuksut. Three years earlier, the Wampanoag had left after a smallpox outbreak ravaged the tribe. The Pahtuksut Wampanoag wait months before approaching the English for help in treating the diseases the colonists brought into their territory.”

They were squatters, not thieves.

An anti-American British site, Mayflower 400, reported, “While the Mayflower’s passengers did not bring slaves on their voyage or engage in a trade as they built Plymouth, it should be recognized the journey took place at a time when ships were crossing the Atlantic to set up colonies in America that would become part of a transatlantic slavery operation.”

How brave to oppose slavery — nearly 160 years after the USA ended it following a bloody civil war that killed 600,000 Americans.

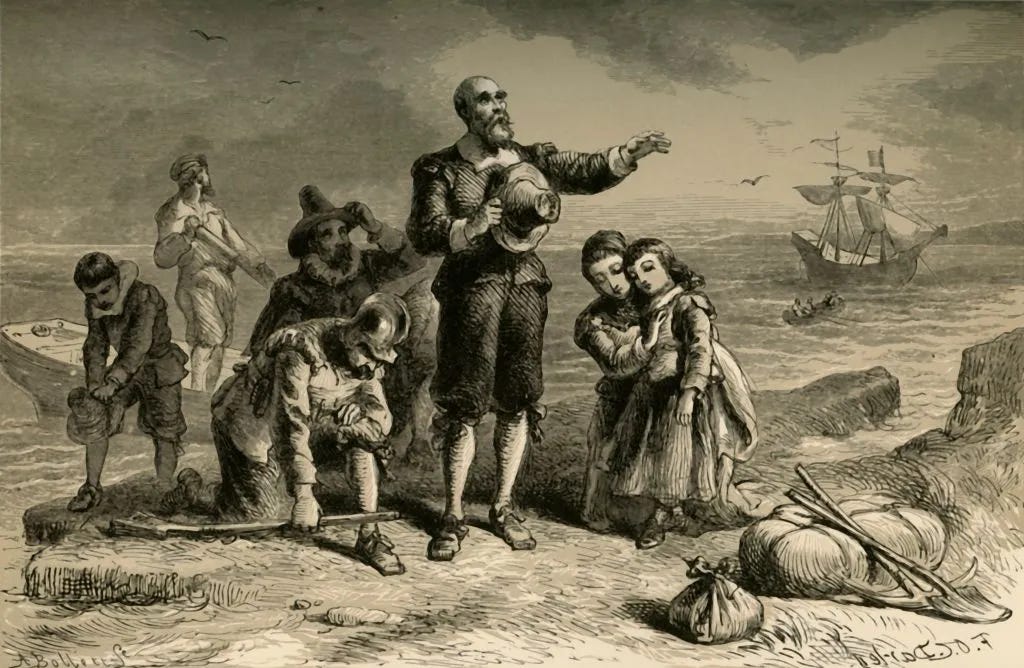

And whose ships were these? British. In fact, the Pilgrims themselves were British subjects who rebelled against the Church of England and King James I. By mutual agreement, the Pilgrims went to live in exile in America. Their original destination was the Hudson River. Storms blew them off course and after 66 days of bobbing in the Atlantic and taking on water, they arrived at Cape Cod. Unable to settle there, they searched for another 43 days for a suitable settlement, and landed at Plymouth Rock on December 21, 1620.

Providence had intervened but their timing was terrible. It was the first day of winter.

The History Channel threw shade on Plymouth Rock, “Plymouth Rock never fails to underwhelm, leaving tourists struck by disappointment rather than awe. But don’t blame the rock. America’s most famous piece of granite is simply a victim of outsized expectations. The overhyped legend surrounding the Pilgrims’ supposed landing place conjures visions of the Rock of Gibraltar. The reality, however, is that the country’s birthstone is a mere boulder.

“And then there’s the inconvenient truth that no historical evidence exists to confirm Plymouth Rock as the Pilgrims’ steppingstone to the New World. Leaving aside the fact that the Pilgrims first made landfall on the tip of Cape Cod in November 1620 before sailing to safer harbors in Plymouth the following month, William Bradford and his fellow Mayflower passengers made no written references to setting foot on a rock as they disembarked to start their settlement on a new continent.”

Fie. The rock is a symbol of the rocky journey the Pilgrims faced.

They scouted the land and found an abandoned village. Mayflower 400 reported, “They found buried corn, which they took back to the ship, intending to plant it and grow more corn. They also found graves.

“This village they had stumbled upon was once home to the Patuxet people but had since been deserted following the outbreak of disease known as the Great Dying —thought to be a European disease brought to the region by sailors.

“This was a legacy of what the Native American people had already experienced from European colonists in the years prior to the Mayflower.”

There they settled. Half of them died. I can only imagine the depression the short days and the agonizing deaths brought.

History Channel in another report said, “For the next few months, many of the settlers stayed on the Mayflower while ferrying back and forth to shore to build their new settlement. In March, they began moving ashore permanently. More than half the settlers fell ill and died that first winter, victims of an epidemic of disease that swept the new colony.

“Soon after they moved ashore, the Pilgrims were introduced to a Native American man named Tisquantum, or Squanto, who would become a member of the colony. A member of the Pawtuxet tribe (from present-day Massachusetts and Rhode Island) who had been kidnapped by the explorer John Smith and taken to England, only to escape back to his native land, Squanto acted as an interpreter and mediator between Plymouth’s leaders and local Native Americans, including Chief Massasoit of the Pokanoket tribe.”

Please note that I use their critics to tell the tale of the Pilgrims because it lends credence to just how wonderful the Pilgrims were. Do not confuse them with the Puritans who burned witches and such. The Pilgrims were the men and women who established America as a refuge from religious persecution.

Don’t take my word for it. Take the word of the Pilgrims.

The Mayflower Compact which Francis Eaton and 40 other men signed said, “In the name of God, Amen. We, whose names are underwritten, the loyal subjects of our dread Sovereigne Lord, King James, by the grace of God, of Great Britaine, France and Ireland king, defender of the faith, etc. having undertaken, for the glory of God, and advancement of the Christian faith, and honour of our king and country, a voyage to plant the first colony in the Northerne parts of Virginia, doe by these presents solemnly and mutually in the presence of God and one of another, covenant and combine ourselves together into a civill body politick, for our better ordering and preservation, and furtherance of the ends aforesaid; and by virtue hereof to enacte, constitute, and frame such just and equall laws, ordinances, acts, constitutions and offices, from time to time, as shall be thought most meete and convenient for the generall good of the Colonie unto which we promise all due submission and obedience. In witness whereof we have hereunder subscribed our names at Cape-Codd the 11. of November, in the year of the raigne of our sovereigne lord, King James, of England, France and Ireland, the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fiftie-fourth. Anno Dom. 1620.”

Now you know which side of my family gave me my propensity for typos.

Life was rough for the Pilgrims but they had each other. In 1656, Governor William Bradford recalled the founding of their colony that winter.

He wrote, “In these hard and difficult beginnings they found some discontents and murmurings arise amongst some, and mutinous speeches and carriages in other; but they were soon quelled and overcome by the wisdom, patience, and just and equal carriage of things by the Governor and better part, which clave faithfully together in the main. But that which was most sad and lamentable was that in two or three months’ time half of their company died, especially in January and February, being the depth of winter, and wanting [lacking] houses and other comforts; being infected with the scurvy and other diseases, which this long voyage and their inaccomodate condition had brought upon them, so as there died sometimes two or three of a day, in the aforesaid time, that of one hundred and odd persons, scarce fifty remained.”

The Indians did not save them that first winter. They did not meet an Indian until Squanto appeared on March 16, 1621. No, they saved themselves.

Bradford wrote, “And of these in the time of most distress, there was but six or seven sound [healthy] persons who, to their great commendations be it spoken, spared no pains, night or day, but with abundance of toil and hazard of their own health, fetched them wood, made them fires, dressed [prepared] them meat, made their beds, washed their loathsome clothes, clothed and unclothed them; in a word, did all the homely and necessary offices for them which dainty and queasy stomachs cannot endure to hear named; and all this willingly and cheerfully, without any grudging in the least, showing herein their true love unto their friends and brethren. A rare example and worthy to be remembered.”

The Pilgrims were a communal lot. This saved them that first winter but later it almost did them in.

Michael Franc of the Heritage Foundation wrote, “Writing in his diary of the dire economic straits and self-destructive behavior that consumed his fellow Puritans shortly after their arrival, Governor William Bradford painted a picture of destitute settlers selling their clothes and bed coverings for food while others ‘became servants to the Indians,’ cutting wood and fetching water in exchange for ‘a capful of corn.’ The most desperate among them starved, with Bradford recounting how one settler, in gathering shellfish along the shore, ‘was so weak … he stuck fast in the mud and was found dead in the place.’

“The colony's leaders identified the source of their problem as a particularly vile form of what Bradford called ‘communism.’ Property in Plymouth Colony, he observed, was communally owned and cultivated. This system (‘taking away of property and bringing [it] into a commonwealth’) bred ‘confusion and discontent’ and ‘retarded much employment that would have been to [the settlers'] benefit and comfort.’”

That didn’t work. There was a famine that nearly wiped the Pilgrims out in 1623 — two years after the first Thanksgiving. So the Pilgrims decided to divvy up the land. This provided the incentive to farm. They flourished.

Franc wrote, “A profoundly religious man, Bradford saw the hand of God in the Pilgrims' economic recovery. Their success, he observed, ‘may well evince the vanity of that conceit...that the taking away of property... would make [men] happy and flourishing; as if they were wiser than God.’ Bradford surmised, ‘God in his wisdom saw another course fitter for them.’”

Never forget that the Lord guided these men and women, which was why they gave thanks to Him in October 1621.

The History Channel, in yet another report, said, “Most of the attendees at the first Thanksgiving were men; 78 percent of the women who traveled on the Mayflower perished over the preceding winter. Of the 50 colonists who celebrated the harvest (and their survival), 22 were men, four were married women and 25 were children and teenagers.

“The Pilgrims were outnumbered more than two to one by Native Americans, according to Edward Winslow, a participant who attended with his wife and recorded what he saw in a letter, writing: ‘many of the Indians coming amongst us, and amongst the rest their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men.’

“Winslow records eating venison from five deer killed by the Native Americans along with chestnuts, cranberries, garlic and artichokes—all native wild plants the English were learning to use. Turkey was potentially served as well.”

The Smithsonian confirmed this, citing Governor Bradford’s diary, which said, “And besides waterfowl there was great store of wild turkeys, of which they took many, besides venison, etc. Besides, they had about a peck a meal a week to a person, or now since harvest, Indian corn to that proportion.”

The story of the Pilgrims is one of hardship, perseverance and faith in God. It includes a rejection of communism and the triumph of private ownership, self-reliance and hard work. They indeed went forth and multiplied. BBC said there are as many as 35 million descendants of the Pilgrims.

The Pilgrims were devoted to God. They left behind everything they knew to make a journey in a small, crowded ship across a storm-tossed sea to a land unknown. They truly were Pilgrims and their pilgrimage showed a faith in the Lord that should shame us all. In God they trusted and with God they succeeded.

Well, you can see why socialists and other revisionists want to discredit the Pilgrims. Historian David Silverman wrote a book, This Land Is Their Land: The Wampanoag Indians, Plymouth Colony, and the Troubled History of Thanksgiving.

He told Claire Bugos of the Smithsonian, “Most poignantly, using a shared dinner as a symbol for colonialism really has it backward. No question about it, Wampanoag leader Ousamequin reached out to the English at Plymouth and wanted an alliance with them. But it’s not because he was innately friendly. It’s because his people have been decimated by an epidemic disease, and Ousamequin sees the English as an opportunity to fend off his tribal rebels. That’s not the stuff of Thanksgiving pageants. The Thanksgiving myth doesn’t address the deterioration of this relationship culminating in one of the most horrific colonial Indian wars on record, King Philip’s War, and also doesn’t address Wampanoag survival and adaptation over the centuries, which is why they’re still here, despite the odds.”

Excuse me, but the Pilgrims are still here, too, despite the odds. They did not steal the land. They did not bring in slaves. They worshipped the Lord, which I believe is the real reason behind the revisionism.

Thanksgiving has always been my most favorite holiday celebration, mainly because it centers around three things of utmost value: faith, family and food. Doesn’t get better than that.

Also, the true history of the Pilgrims is one the most inspiring, embracing almost incomprehensible courage, faith, and fortitude. The strength and determination of those people, buoyed only by their faith in the One, True God is something we could all well learn now to embibe as we all in these present times most assuredly are heading into a long winter of much discontent (and I don’t mean just the season).

Great story, Don. You're right about the revisionists wanting to get rid of the Pilgrims' devotion to God. Their collectivism almost killed them, but that's the story the revisionists would prefer to be the truth. But it was not to be, thankfully. An early Happy Thanksgiving to all. Despite the current gloom, there's so much to be grateful for in our world.