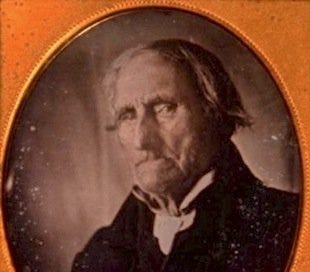

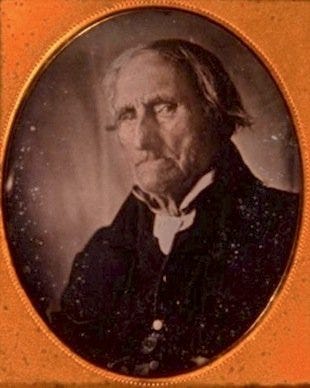

The old farmer was there with Washington when he crossed a frozen Delaware River in blizzard-like conditions on Christmas 1776. And so the photographer took a daguerreotype photo of Conrad Heyer in 1852, who 103 years early was the first European child born in Waldoboro, Maine. At 24, he had enlisted in the Continental Army and spent 1776 with Washington, whose rag-tag army went from victory in Boston to defeat in New York to a daring raid and stunning victory in the Battle of Trenton, New Jersey.

The New Market Press reported on July 25, 2013, “According to the Maine Historical Society, Heyer may be the earliest born human being ever photographed. He is also the only U.S. veteran to be photographed who crossed the Delaware River alongside George Washington in December 1776.”

There is some dispute as to whether he was the earliest born person to be photographed. Three claims of earlier birth have been made, including a slave who would have been 115 when photographed.

But there is no dispute about Heyer’s service to our country. He was a farm boy who became one of thousands of patriots who took up arms to force the best army in the world to leave the colonies so that Founding Fathers could set up a government that protected our rights.

On December 25, 1776, Heyer participated in the Most American Christmas Ever when Washington crossed the Delaware River, raided Trenton and caught 1,400 Hessian troops — who fought for the British — napping.

Heyer and the rest of the Yankee troops gathered at the river around 6 p.m. on that Christmas day for what was to be three crossings of the river. The plan was to ferry 5,400 troops and equipment but bad weather forced them to cancel the second and third crossings.

You can be darned sure that Washington was in the first crossing, along with his logistics magician Henry Knox who would serve as President Washington’s secretary of war. They named a lot of things after Knox and for good reason. He might not have been able to pull off the impossible, but the improbable was a piece of cake for him.

In 1775, Washington was stuck outside of Boston unable to persuade the British army to leave. What he needed was some artillery to convince them. Isaac Makos is an Interpretive Supervisor at George Washington's Mount Vernon. He wrote about Knox doing the improbable and getting artillery to Washington.

Makos wrote, “Nearly 300 miles away, on the shore of Lake Champlain, was a treasure trove of artillery. In May of 1775, Ethan Allen led a militia made up of settlers from present-day Vermont, called the Green Mountain Boys, in a surprise attack that captured Fort Ticonderoga and its small British garrison without firing a shot. With this act of ‘burglarious enterprise,’ as one British writer described it, the rebels took possession of 200 cannons. Most officers thought that moving the guns all the way from Fort Ticonderoga to Boston was impossible, but Henry Knox thought otherwise.”

Knox was a bookseller in Boston who joined the Continental Army and impressed Washington. Makos wrote, “Knox went to Washington and confidently predicted that once the cannons had been taken by boat from Fort Ticonderoga to the southern end of Lake George, it would take fewer than 20 days to move them overland to Boston.”

Washington approved the plan and Knox left for Fort Ticonderoga on November 16, 1775. When he arrived, it was winter. The snow was like a doctoral dissertation: Piled High and Deep. Knox would use that to his advantage.

Makos wrote, “He selected 58 pieces of artillery to take back to Boston. Most of artillery pieces were 12-pounder or 18-pounder cannons (depending on the weight of the cannonball they fired). Knox also brought one massive 24-pounder cannon, nicknamed Old Sow, that weighed more than 5,000 pounds and several high-arching mortar guns that weighed one ton each. In total, Henry Knox’s noble train of artillery weighed 120,000 pounds, or 60 tons.”

Ferrying the freight across the lake was hard work but it was easy compared to the task before him. He had to get to Boston through heavy snow.

Makos wrote, “Knox and his men used more than one-half mile of rope to secure the guns to 42 sleds. Hauling the heaviest guns required eight horses and sometimes additional oxen as well.

“The journey on land required crossing the frozen Hudson River four times. The leader of each sled team carried an axe, so that if a cannon fell through the ice they could cut the lines before it dragged the horses underwater as well. Henry Knox himself nearly froze to death while trying to walk through three feet of snow in a blizzard.”

But he got the artillery to Boston and won the Siege of Boston. The nearly year-long battle was a stalemate until those cannon arrived. Washington placed them strategically and the British awoke on March 4, 1776, to cannon staring at them. 13 days later, the British decided to re-locate to New York. While the rest of the world celebrates St. Patrick’s Day, a few people in Boston still refer to March 17 as Evacuation Day. (New York’s E-Day is celebrated on November 25, the date in 1783 when the British finally quit the city.)

T. Logan Metesh is a historian with a focus on firearms history and development. One year ago, he pointed out that 1776 was a terrible year for the Americans.

He wrote, “As 1776 drew to a close in mid-December, Gen. Washington and his soldiers were at a low point, and the American Revolutionary War wasn’t going well for the Continental Army. They had been defeated at New York City, forced to retreat through New Jersey, and found themselves encamped back in Pennsylvania along the Delaware River as winter set in hard.

“The soldiers had been repeatedly defeated; it was getting increasingly colder, clothing was worn thin, and food was in short supply. The Continental soldiers were feeling pretty damn miserable at this point. For many, the only glimmer of hope was that their enlistments would be up come January 1777, and they could put this whole soldiering mess behind them. Washington knew that he needed to do something to help boost the morale of his men and try to end the year on a high note.”

Washington made the decision. Knox made it possible.

Crossing a frozen river in the middle of the night is no easy task.

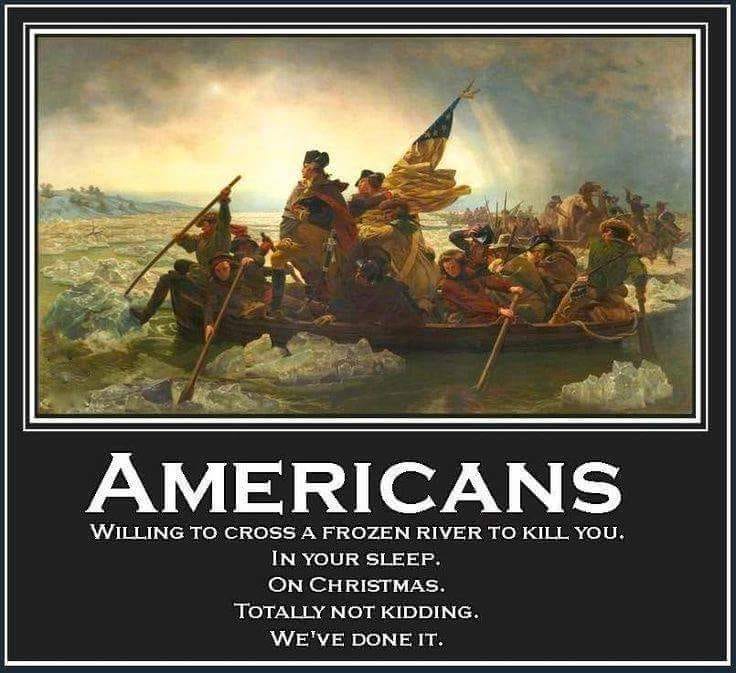

Metesh wrote, “Around 6 p.m., the daring plan was set into motion, but the weather had taken an abysmal turn. Winds howled out of the northeast carrying sleet and snow with it, temperatures hovered around 30 degrees, and the Delaware River became choked with ice. In short, the crossing would be no cakewalk, and victory was far from assured.

“A large portion of Washington’s men crossed the river in Durham boats, which were larger than Leutze’s painting depicts — they were 40 to 60 feet long, 6 feet wide, and 3 feet deep with flat bottoms, and weighed thousands of pounds. They were pointed at both ends and designed to travel up and down the river hauling cargo. They were propelled along the shoreline by plating steel-tipped poles in the riverbed and oars were used in deeper water. The boats took some skill to steer, even in good weather.

“The plan suffered some serious blows early on, in addition to the leak. There were supposed to be three separate crossings, but two of them were unable to make it across due to the river ice. Only the group that included Washington himself would actually forge ahead.”

Metesh referred to Emanuel Leutze’s 1851 painting, Washington Crossing the Delaware. Shown is George Caleb Bingham’s less famous rendition.

When they landed and reformed, they were three hours behind schedule. The storm turned a 10-mile march into a four-hour ordeal.

History.com reported, “At approximately 8 a.m. on December 26, Washington’s remaining force, separated into two columns, reached the outskirts of Trenton and descended on the unsuspecting Hessians. Trenton’s 1,400 Hessian defenders were groggy from the previous evening’s festivities and underestimated the Patriot threat after months of decisive British victories throughout New York. Washington’s men quickly overwhelmed the Germans’ defenses, and by 9:30 a.m. the town was surrounded. Although several hundred Hessians escaped, nearly 1,000 were captured at the cost of only four American lives. However, because most of Washington’s army had failed to cross the Delaware, he was without adequate artillery or men and was forced to withdraw from the town.

“The victory was not particularly significant from a strategic point of view, but news of Washington’s initiative raised the spirits of the American colonists, who previously feared that the Continental Army was incapable of victory.”

The morale boost continues today. People use the Internet to boast about a victory by others nearly a quarter of a millennium ago.

But when I look at that daguerreotype of a grizzled Conrad Heyer, I think hell yeah. Even at 103, he would kill you in your sleep if he had to. On Christmas.

The Most American Christmas Ever may not have involved elves, reindeer or a Red Ryder Daisy BB Gun, but that battle helped deliver the second-greatest Christmas gift (after the birth of Jesus, of course) for Americans.

Liberty.

Merry Christmas!

Luke 2:14 “Glory to God in the highest,

and on earth peace among those with whom he is pleased!”

And a fiery sneak attack to the rest of you. :-)

Really enjoying your longer articles. Just trying to find time to get through them all can be a challenge. Happily we have until next week for your next installment. Your wise words would meet a far larger audience if I had anything to do with it.

You Don Surber and Donald Trump are about the only two people outside family that I trust - and some of them are kinda shaky ;-) Merry Christmas from the Edwards in Chattanooga and keep at least until the Biden plague has passed.