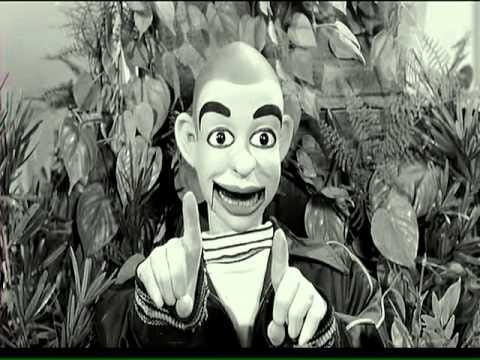

Wednesday marks the centennial of the birth of Paul Winchell in Manhattan's Lower East Side. He was a ventriloquist and a pioneer of television. He and his dummies became a staple of Saturday morning TV. He included in his show quizzes and adventure segments.

When cartoons replaced variety and adventure shows for kids, he did cartoon work. He voiced Gargamel in The Smurfs cartoons and Dick Dastardly in the Wacky Races cartoons. His best work was as Tigger in the Winnie the Pooh movies and shorts, winning a Grammy for his performance in Winnie the Pooh and Tigger Too. He also was part of the Oscar-winning Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day.

Woo-hoo!

But Winchell’s life went far beyond entertainment. He took on the powerful Metromedia all the way to the Supreme Court — and won $17.8 million.

Winchell also held 30 patents. His inventions include a disposable razor, a flameless lighter and an artificial heart which was the basis for the Jarvik-7, the first successful artificial heart. Although Robert Jarvik denied it, Dr. Henry Heimlich (of Heimlich maneuver fame) stated, “I saw the heart, I saw the patent and I saw the letters. The basic principle used in Winchell's heart and Jarvik's heart is exactly the same.”

The controversy was over ego not money because Winchell had donated the patent to the University of Utah, where Jarvik worked.

Paul Winchell (nee Paul Wilchinsky) had a poor childhood. Not only was his family impoverished, but his mother was mean. That helped him overcome polio, which struck him at age 6. She forced him to strengthen his legs. But when he was 12, she refused to give him a dime to buy a book on ventriloquism. Fortunately an older sister gave him the 10 cents he needed. Thanks to his sister, baby boomers who grew up in the 1950s and 1960s had a happier childhood.

At 12, his art teacher, Jero Magon, encouraged him to build a dummy, which Winchell named Jerry Mahoney in Mister Magon’s honor. Winchell wrote, “I didn't tell anyone that I'd learned ventriloquism during the last few months. I simply picked up the head and began to make it talk. My classmates were astounded and watched in awe as I began to imitate Charlie McCarthy's voice. . . . I'd never been particularly popular in school, but suddenly I had found my place in the sun.”

He later won first place on Major Bowes Amateur Hour. This kicked off the ventriloquist’s career in show business. A radio show failed in 1943 but a few years later, television beckoned and he was ready for it. Jerry Mahoney was a smart aleck, so Winchell added the slow-witted Knucklehead Smiff to his cast. This mirrored Edgar Bergen’s Charlie McCarthy and Mortimer Snerd.

Under various names, his TV show aired in prime-time from 1950 to 1954 before being relegated to Saturday mornings. Carol Burnett was a regular on the show in 1955. She later recalled, “I was a sort of girlfriend to the dummies.” Peter Lorre was among the others who acted on his show. Winchell, too, guest-starred as he branched out as an actor with roles on Perry Mason, the Beverly Hillbillies, and The Lucy Show.

He even voiced a Scrubbing Bubble.

Woo-hoo!

As successful as was in TV, Winchell always wanted to be a doctor. He grew up in the wrong time. He said, “it was the Depression, there was no money and my ventriloquist hobby just took off.” In 1955, at age 32, he enrolled at Columbia University. That was where he met and became friends with Heimlich. Winchell’s interest was in acupuncture and medical hypnosis, as well as inventing that artificial heart in 1963.

The American Heart Association was not interested in his heart. He said on the Sally Jesse Raphael Show decades later, “They told me, ‘The day you come in here with a sheep on a leash with an artificial heart, we'll give you the grant.’”

19 years after that rejection, the first artificial heart was transplanted into Barney Clark.

In his autobiography, Winch, Winchell said, “Odd as it may seem, the heart wasn't that different from building a dummy; the valves and chambers were not unlike the moving and eyes and closing mouth of a puppet.”

He also won an important legal case. In a dispute over syndication rights, Metromedia destroyed the tapes of his TV show. The Los Angeles Times reported on July 6, 1986, “Ventriloquist Paul Winchell won a $17.8-million verdict Wednesday in a decade-long fight against Metromedia Inc., which he claims destroyed the only remaining tapes of his popular Winchell Mahoney Time children’s television series in a dispute over syndication rights.”

The Supreme Court refused to hear Metromedia’s appeal, which upheld the lower court’s ruling.

He told the Los Angeles Times, “The thing that was perhaps most painful to me was that in my best days, back in the ‘50s and ‘60s, it was all live.

“All the work I had done in the past, there was no record of it. Then finally I had the opportunity to do this taped thing, and I felt that at last, I’ll have some remaining record of my work that future people could see, especially children.

“Suddenly, I didn’t have it anymore. It was gone forever.”

He was right. Those executives robbed generations of children.

But as successful as he was in so many fields — entertainment, inventions and writing — Winchell never seemed to find happiness. Maybe this was from a poor childhood. Maybe this was a side effect of ventriloquism. All I know is that in a 1954 interview, Winchell said, “Gradually I found myself faced with the dilemma that comes to most ventriloquists. I was snowed under by the personality of the dummy. Mail began to pour in to Paul Mahoney and Jerry Winchell. I was Jerry's straight man.

“Everybody knew who Jerry was, but they were beginning to forget the name of the guy who operated him. To that extent it was jealousy.”

He was hospitalized briefly for depression and in the end, estranged from his three children.

In his song Celluloid Heroes, Ray Davies wrote:

You can see all the stars as you walk down Hollywood Boulevard

Some that you recognize, some that you've hardly even heard of

People who worked and suffered and struggled for fame

Some who succeeded and some who suffered in vain

Winchell worked and suffered and struggled for his art.

He died on June 24, 2005, at the age of 82. His youngest child, April, wrote, “My father was an extremely gifted man. He did amazing things with his intellect. He contributed not only to television, but to medicine, society and technology. Some of you have even said that he was infinitely more talented than I will ever be. You're probably right. But I was never in competition with him, nor am I jealous of his accomplishments. I am very, very proud of them. I can honestly say that he left this world a better place than he found it.

“I sometimes wish I too, could have had the experience others had of him. If I could have known only his public persona, I'm sure I would have had nothing but warm and happy memories of him. I envy you that.

“But you must be fair and understand that he was my father. And even in the best of circumstances, no one has an idyllic, uncomplicated, painless relationship with a parent.

“And these were not the best of circumstances. This was a terrible situation for all concerned. Every one of my siblings suffered more than you will ever know.”

Unhappy childhoods run in his family.

But oddly enough, he brought much joy to the lives of other children — and life to many heart patients.

Woo-hoo!

Marvelous and totally unanticipated revelation about a man whose contributions to the society in which he lived have largely gone unheralded. I recall being always amused as Knucklehead Smiff gazed in abject befuddlement at his ventriloquist after some utterly banal comment from "Mr. Winkle." I had no idea that "Mr. Winkle" was so multifaceted and intelligent. Thank you for sharing this. It reminds me to never judge a book by its cover. Well, I admit that there are some occasions when that is acceptable, but not in this one.

I learned something here although I grew up with Jerry Mahoney. In fact, one year I got a Jerry Mahoney dummy for Christmas. It was great fun. I had no idea of Paul Winchell's many accomplishments. Thank you for providing this education.